This post is an introduction to the Bundelkhand region. I hope that it will contribute to raising awareness about this region and discover some of its hidden treasures.

Geography of Bundelkhand

The northern part of this region lies in the state of Uttar Pradesh (purple in the map below) while its southern part lies in the state of Madhya Pradesh (green in the map).

It is a Hindi speaking area. The Bundeli language is the most common of the Hindi dialects spoken in the area. It in turn consists of several sub-dialects.

A Brief History of Bundelkhand

Oral histories and legends of the region describe it as the ancient reign of king Luv, the son of Lord Rama. In the Pre-Buddhist period, this area came under the kingdom of Ujjain.

In the Buddhist period (around 500 BCE), this area was known as Chedi Janapada (literally "Ruled by the people") as shown in Thomas Lessman map of 500 BCE.

Chandelas arrived here in the 9th century as the feudal lords of the Pratihara, however soon they became independent. They ruled Bundelkhand for around 300 years. Initially they ruled from Khajuraho and then shifted to Mahoba. They built the famous Khajuraho temples in the 10th century, and the fort and a few artificial lakes in Mahoba in the 11th-12th centuries. In late 12th century, as their power weakened, a part of Bundelkhand came under the Khangar dynasty, who took over the Jingarh fortress of the Chandelas and renamed it Garh Kundhar.

In early 13th century the Chandelas were defeated by the sultan of Delhi, Qutubuddin Aibek, who was of Turkish origins. After almost two centuries, in the 16th century, for a short period the Chandela dynasty rose again, but it could not last and during the reign of Akbar, the region passed under the Mughal empire.

As part of the empire, Bundelkhand was ruled by Rajput kings, who recognized the Mughal sovereignty. (Below, Thomas Lessman map from 1500 CE showing the Rajput states). These kings are known as Bundela kings and this was the period, when the region got its name Bundelkhand. Bundela kingdoms started in Orchha, moved to Chattarpur and then to Jhansi.

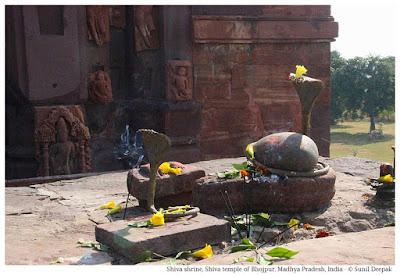

Temples, Shrines and Dargahs of Bundelkhand

The region is predominantly Hindu. Earlier temples attest to the strong presence of Shaivism in the region with a number of Shiva temples. The image below shows an old Shiva temple in the lower parts of the Jhansi fort.

Forts of Bundelkhand

Bundelkhand region is full of ruins of magnificent fortresses and temples, many of which are known only to local persons and to academics.

For example, according to Dr Ramsajivan who wrote a PhD thesis on this theme in 2006, there are 41 important fortresses in Bundelkhand - Kalinjar, Ajaygarh, Rasin, Madfa, Sherpur Sevda, Rangarh, Tarhua, Bhuragarh, Mahoba, Sirsagarh, Jaitpur, Mangalgarh, Maniyagarh, Baruasagar, Orchha, Jhansi, Garh Kundhar, Chirgaon, Airch, Urai, Kalpi, Datiya, Badhoni, Gwalior, Chanderi, Chhattarpur, Panna, Singhorgarh, Rajnagar, Batiyagarh, Bajawaor (Jatashanker), Beergarh, Dhamoni, Patharigarh (Patharkachhar), Barigarh, Gaurhar, Kulpahar, Talbehat and Devgarh.

The descriptions of some of these forts, hardly visited by the tourists, are beautiful. For example - the ruins of Ajaygarh fort are located on a verdant hill and are difficult to reach while the Rangarh fort, built on a picturesque hill on an island of Ken river near Pangara, is surrounded by thick forests. Finding information about these places and reaching them is difficult.

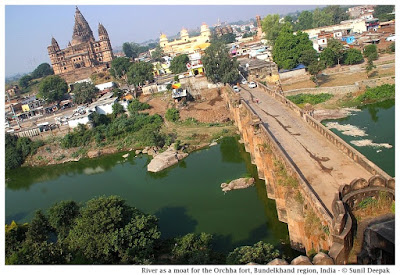

Building of the forts followed guidelines given in India's ancient architecture texts of Vaastu Shastra. These forts had thick high walls and were surrounded by moats or natural barriers such as rivers. The image below shows a branch of Betwa river that separates the Orchha fort from the town.

Inside, these forts usually had ponds at different levels, both above and below, for their water supply. The ponds were usually accompanied by a temple. The image below shows a beautiful small pond from the Gwalior fort.

Conclusions

Bundelkhand is not an easy region to visit. Being at the border of two states, many towns of the region are not well connected. It is a drought prone area and one of the poorest parts of India. Except for Gwalior, Jhansi, Orchha and Khajuraho, most of its rich history and monuments are ignored and neglected.

I hope that this post will stimulate some of you to visit and document some of its lesser known places and monuments.

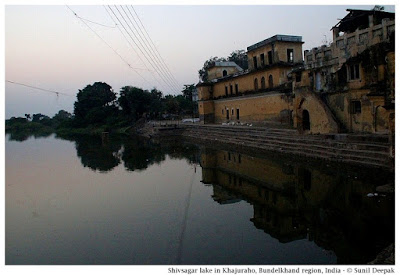

Let me conclude this post with an image (above) of the beautiful Shiv Sagar lake built under the Chandela dynasty in Khajuraho.

***

Bundelkhand region is full of ruins of magnificent fortresses and temples, many of which are known only to local persons and to academics.

For example, according to Dr Ramsajivan who wrote a PhD thesis on this theme in 2006, there are 41 important fortresses in Bundelkhand - Kalinjar, Ajaygarh, Rasin, Madfa, Sherpur Sevda, Rangarh, Tarhua, Bhuragarh, Mahoba, Sirsagarh, Jaitpur, Mangalgarh, Maniyagarh, Baruasagar, Orchha, Jhansi, Garh Kundhar, Chirgaon, Airch, Urai, Kalpi, Datiya, Badhoni, Gwalior, Chanderi, Chhattarpur, Panna, Singhorgarh, Rajnagar, Batiyagarh, Bajawaor (Jatashanker), Beergarh, Dhamoni, Patharigarh (Patharkachhar), Barigarh, Gaurhar, Kulpahar, Talbehat and Devgarh.

Building of the forts followed guidelines given in India's ancient architecture texts of Vaastu Shastra. These forts had thick high walls and were surrounded by moats or natural barriers such as rivers. The image below shows a branch of Betwa river that separates the Orchha fort from the town.

Bundelkhand is not an easy region to visit. Being at the border of two states, many towns of the region are not well connected. It is a drought prone area and one of the poorest parts of India. Except for Gwalior, Jhansi, Orchha and Khajuraho, most of its rich history and monuments are ignored and neglected.

I hope that this post will stimulate some of you to visit and document some of its lesser known places and monuments.

***