Indian society is made of hierarchies of class. We keep on judging persons and mentally classifying them if they are above us, at our same level or are below us. It happens inside our families, in our work places, when we go out, when we meet someone. This classification decides how we behave with them.

I am arguing that this class-based mindset is a barrier to development of India.

For the past few days, since the 23 year old girl was brutally raped and dumped from a moving bus in Delhi, I have been reading about the growing public outrage and protests, as well as, the reflections of persons about it.

For example, Shoma Chaudhury from Tahelka has written in her opinion piece:

How does it matter if the girl who is raped is a medical student or is studying to be a lab technician or a nursing assistant? And, why do newspaper or magazine have to specify it every time they write about it? Isn’t it enough to say “a young girl”? or a university student?

I can understand that when the news broke out, newspaper had to provide some information about the girl and her background. But why do they need to keep on specifying it, or rather, defining the girl in terms of her studies?

I feel that one of the reasons why we keep on specifying the study course of that girl is because we are very class-conscious. After visiting a number of countries in different continents, I think that Indian society is one of the most class-conscious societies in the world.

Perhaps the most defining criteria of this class consciousness is persons’ socio-economic background, their professions, incomes, etc. We behave differently with people who work as waiters, drivers, security guards, domestic helpers, cleaners etc. compared to how we behave with people higher up in hierarchy.

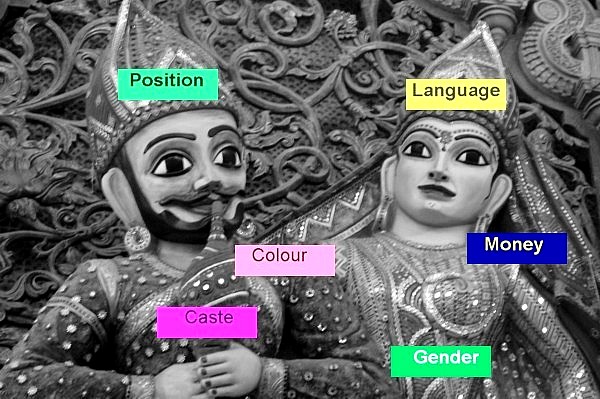

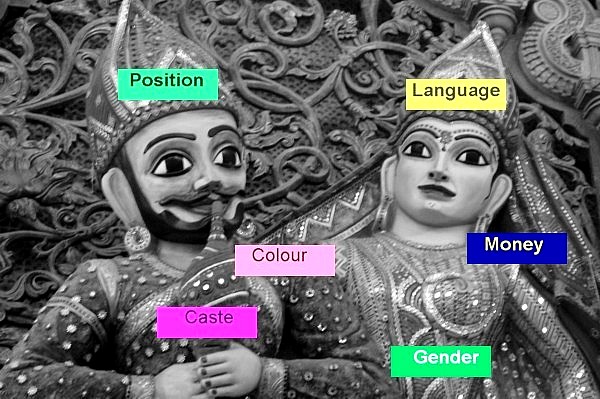

However, there are many other criteria to classify people and to calculate their relative place in the world around us. Gender is one such criteria, women are lower in hierarchy. If women claim higher hierarchical space, because of their socio-economic status, as soon as there is an opportunity, men placed lower down on their hierarchy, feel justified to “put them in their place”. Groping, violence and rape are some ways of putting women in their place.

Caste is another criteria for defining your place in the hierarchy of the Indian society. Comparatively, some attention has been given to issues related to caste discrimination. For those placed in the lowest margins of the caste system, parts of Indian society have asked for the removal of untouchability and affirmative action for their inclusion in areas of education and livelihood. However, we do not seem to have any problems with caste system if these "extremes" can be corrected. I wonder if only overcoming the stark discriminations against Dalits, would make the remaining caste-based hierarchies acceptable?

The language we speak, and the clothes we wear are other markers of our place in the social hierarchy. In “English Vinglish”, Shashi (Sridevi) says with a wry smile, “Important things are discussed only in English.” If you can’t speak English properly, you lose your place in the social hierarchy in India. Just a look at the smug publicity of “English medium” schools and the demand for “convent school educated” brides in the matrimonial columns is enough to state the obvious superiority of English. Even the poor and the uneducated persons know this and are willing to make sacrifices so that their children can repeat English nursery rhymes.

Every now and then I receive congratulatory messages from friends and acquaintances for “writing in Hindi”. I don’t know if there is another country in the world, where people are congratulated for their skills in writing or talking in their mother tongue, and where not being able to speak properly in the mother tongue is seen as sign of higher social status.

If Hindi is much lower compared to English in our social hierarchy, Hindiwallas look disdainfully at those who speak Maithili or Bhojpuri. Speaking sanskritized Hindi or refined Urdu is higher social status marker compared to those speak ordinary Hindustani.

Being from a big city, compared to being from a hinterland city or worse, being from a village, the colour of your skin, etc. are also markers of social status. This list of criteria for defining your place in social hierarchy goes on and on.

Unfortunately, these differences are not about human diversity, but they affect every aspect of our lives. For example, they determine, the kind of jobs you can have, the kind of news-worthiness you will have, and how the Indian system will treat you in your daily life.

There have been many social reformers in India who have spoken about the negative role of untouchability and caste exclusion, but there has been much less debate about the our rigid class-hierarchies and the impact these have on our lives and on our nation. One exception to this was Swami Vivekanand. Mr. Pranav Mukherjee, president of India, recently wrote in an article in the Week about the 150 birth anniversary of Swami Vivekanand:

Everyone in this system has some one else who is lower in some kind of hierarchy from them. While we chafe at the highhandedness and callousness of those above us, we are equally brutal in our behaviour towards those who we perceive as lower than us.

How can we break these barriers? Can India truly develop without breaking down these barriers?

***

I am arguing that this class-based mindset is a barrier to development of India.

For the past few days, since the 23 year old girl was brutally raped and dumped from a moving bus in Delhi, I have been reading about the growing public outrage and protests, as well as, the reflections of persons about it.

For example, Shoma Chaudhury from Tahelka has written in her opinion piece:

THE SURGING outrage at the gangrape of a paramedic in New Delhi this week is welcome and cathartic. But it is also terrifying. There’s a fear that this too shall fade without correctives. But there is also a question we must all face: why did it need an incident so unspeakably brutal to trigger our outrage? What does that say about our collective threshold as a society? Why did hundreds of other stories of rape not suffice to prick our conscience?

The harsh truth is, rape is not deviant in India: it is rampant. The attitude that enables it sits embedded in our brain. Rape is almost culturally sanctioned in India, made possible by crude, unthinking conversations in every strata of society. Conversations that look at crime against women through the prism of women’s responsibility: were they adequately dressed, were they accompanied by a male protector, were they of sterling ‘character’, were they cautious enough.Something about these discussions in the newspapers and magazines has intrigued me – while talking about the victim of the rape, they always add that she is “a paramedic”. Initial newspaper reports had talked about her being “a medical student”. Later on, reporters must have discovered other information and had become more specific – the girl is not a medical student but a paramedical course student.

How does it matter if the girl who is raped is a medical student or is studying to be a lab technician or a nursing assistant? And, why do newspaper or magazine have to specify it every time they write about it? Isn’t it enough to say “a young girl”? or a university student?

I can understand that when the news broke out, newspaper had to provide some information about the girl and her background. But why do they need to keep on specifying it, or rather, defining the girl in terms of her studies?

I feel that one of the reasons why we keep on specifying the study course of that girl is because we are very class-conscious. After visiting a number of countries in different continents, I think that Indian society is one of the most class-conscious societies in the world.

Perhaps the most defining criteria of this class consciousness is persons’ socio-economic background, their professions, incomes, etc. We behave differently with people who work as waiters, drivers, security guards, domestic helpers, cleaners etc. compared to how we behave with people higher up in hierarchy.

However, there are many other criteria to classify people and to calculate their relative place in the world around us. Gender is one such criteria, women are lower in hierarchy. If women claim higher hierarchical space, because of their socio-economic status, as soon as there is an opportunity, men placed lower down on their hierarchy, feel justified to “put them in their place”. Groping, violence and rape are some ways of putting women in their place.

Caste is another criteria for defining your place in the hierarchy of the Indian society. Comparatively, some attention has been given to issues related to caste discrimination. For those placed in the lowest margins of the caste system, parts of Indian society have asked for the removal of untouchability and affirmative action for their inclusion in areas of education and livelihood. However, we do not seem to have any problems with caste system if these "extremes" can be corrected. I wonder if only overcoming the stark discriminations against Dalits, would make the remaining caste-based hierarchies acceptable?

The language we speak, and the clothes we wear are other markers of our place in the social hierarchy. In “English Vinglish”, Shashi (Sridevi) says with a wry smile, “Important things are discussed only in English.” If you can’t speak English properly, you lose your place in the social hierarchy in India. Just a look at the smug publicity of “English medium” schools and the demand for “convent school educated” brides in the matrimonial columns is enough to state the obvious superiority of English. Even the poor and the uneducated persons know this and are willing to make sacrifices so that their children can repeat English nursery rhymes.

Every now and then I receive congratulatory messages from friends and acquaintances for “writing in Hindi”. I don’t know if there is another country in the world, where people are congratulated for their skills in writing or talking in their mother tongue, and where not being able to speak properly in the mother tongue is seen as sign of higher social status.

If Hindi is much lower compared to English in our social hierarchy, Hindiwallas look disdainfully at those who speak Maithili or Bhojpuri. Speaking sanskritized Hindi or refined Urdu is higher social status marker compared to those speak ordinary Hindustani.

Being from a big city, compared to being from a hinterland city or worse, being from a village, the colour of your skin, etc. are also markers of social status. This list of criteria for defining your place in social hierarchy goes on and on.

Unfortunately, these differences are not about human diversity, but they affect every aspect of our lives. For example, they determine, the kind of jobs you can have, the kind of news-worthiness you will have, and how the Indian system will treat you in your daily life.

There have been many social reformers in India who have spoken about the negative role of untouchability and caste exclusion, but there has been much less debate about the our rigid class-hierarchies and the impact these have on our lives and on our nation. One exception to this was Swami Vivekanand. Mr. Pranav Mukherjee, president of India, recently wrote in an article in the Week about the 150 birth anniversary of Swami Vivekanand:

Before he went to America in 1893, Swamiji spent a few years travelling all over India as a wandering monk. During these travels he was deeply moved by the destitution and backwardness of millions of ordinary Indians. However, he also saw that, in spite of poverty, the ancient spiritual culture was a powerful force in their lives. Swamiji concluded that the real cause of India's backwardness was the neglect and exploitation of the masses who produced the wealth of the land…Swamiji was intensely pained at the caste discrimination prevalent in India and full of sympathy for the poor and suffering of all nations, castes and creeds. He held the neglect of the masses and the subjugation of women to be the two causes of India's downfall.Living in India, often it is difficult to become aware of these class hierarchies that permeate our lives. They are so pervasive and ingrained in our minds that they look like “natural phenomenon”, something god-given and thus, impossible to change.

Everyone in this system has some one else who is lower in some kind of hierarchy from them. While we chafe at the highhandedness and callousness of those above us, we are equally brutal in our behaviour towards those who we perceive as lower than us.

How can we break these barriers? Can India truly develop without breaking down these barriers?

***